July 2024: Higher taxation to impact intrinsic value

In 2024

- December 2024: The primary market – the raison d’être of the secondary market

- November 2024: A glimpse into Sep-24 quarterly earnings

- October 2024: Weak Market Internals

- September 2024: Implications of Fed rate cut

- August 2024: BSE500 constituents trading at elevated valuations

- July 2024: Higher taxation to impact intrinsic value

- June 2024: Risks to the market and our process to handle them

- May 2024: Corporate Results Trends over the last 10 years

- April 2024: Our investment process explained through AMCs

- March 2024: Market cap to GDP – where is India in terms of valuation

- February 2024: Patience – a virtue in the investment journey

- January 2024: Party continues for mid caps, small caps and PSUs

The Finance Minister presented the budget for the year on 23rd July, 2024 which had many interesting features like a promotion of skilling and prompting the top 500 companies to hire interns from their CSR obligations. However, we want to focus this newsletter on the changes in capital gains taxes which are important for our investors.

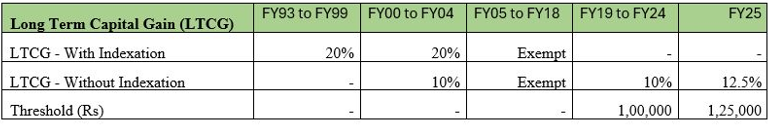

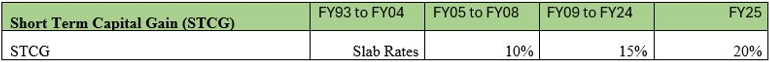

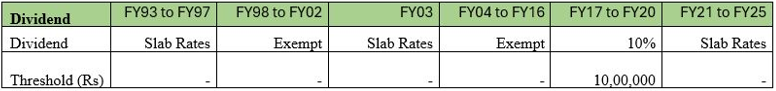

The following tables show how taxation on listed equities has changed over time. In 2004, in a dream move for equity investors, then Finance Minister P Chidambaram, made Long Term Capital Gains (LTCG) tax exempt. He replaced LTCG tax with Securities Transaction Tax (STT), a small charge on each transaction which actually yielded higher revenue to the government than LTCG was doing, at the time. In 2018, the BJP government reintroduced LTCG tax at 10% and now in the current budget, this has been increased to 12.5%. This is now roughly the highest tax on LTCG since 1992. What should be noted here is that the surcharge and cess takes the effective tax rate on LTCG and STCG even higher for those in the higher income tax slabs (not included in below table). Please also note that in the table below, in the years FY2004 to FY2020, when dividend was taxed at a lower rate in the hands of the shareholders, dividend was additionally being taxed in the hands of the company paying the dividends, at rates between 15 to 20% as dividend distribution tax.

In the past, finance ministry officials have given interviews to the press saying that capital gains income is passive income as opposed to hard earned income of people from salary or business and therefore should not be taxed at low rates prevailing from 2004 to 2018. So, in a sense this move by the government is in line with views expressed by the finance ministry officials in the past. Another idea that is proposed is that if interest income is taxed at the marginal tax rate, why should gains from equity, ie capital gains and dividend not be taxed at the same rate?

There are some flaws in these arguments. The money that is invested in equities or debt instruments is money which has already been taxed once, at whatever slab any person falls in the tax structure. So, it is not comparable to salary or business income. The argument about tax on interest income is flawed because the interest income that I am paying tax on, in my income tax return, is an expense item for the bank or other financial services company who is paying me the interest. And similarly, the bank’s interest income is the borrower’s expense which is allowed as a deduction in the income tax calculation. Broadly speaking, the government’s tax revenues from interest income as a whole are close to zero. So, the taxation on interest and equities cannot be equated.

Taxation was also changed for real estate transactions in the budget. Until now, the seller of a property got the benefit of indexation on their cost of purchase in line with inflation and the gains on that basis were taxed at 20%. The indexation benefit has now been removed, for properties bought after 2001, and the gains are now to be taxed at a flat 12.5%. Our rough calculations suggest that if the underlying gain in property value is more than 10% per annum, the new regime is beneficial for the tax payer and if the appreciation in property value is below 10%, the new tax regime will result in a higher tax outgo. While data on historical property appreciation is a bit sketchy (different sources like NHB and RBI give different rates of appreciation), our best guess is that over the last 10-15 years, appreciation in property prices has been below 10% pa (about 2-3% of the return from real estate is from rental yield in India and the rental income is taxed separately) and the new regime will probably result in a higher tax outgo for the investors who have purchased property in the last 10-15 years.

India needs a lot of investment over the next many decades to fulfill the dreams of her people. Continuously increasing tax rates and tinkering with rates and tax policies is not a good recipe to achieve this dream. Higher rates of taxation push up the required pre-tax rate of return that an entrepreneur will require for any capex that he/she is planning. Therefore, fewer projects can cross the higher investment hurdle resulting in lower investment and thereby lower growth in the economy. Moderate and stable taxation policies will go a long way in attracting investment into the economy and help investors plan better and perhaps the government should consider that point of view.

Surprisingly the market despite a brief pullback intra-day on the day of the budget, has swallowed the 25% increase in the taxation on LTCG with ease and has continued to march ahead. We guess, bull markets are like that. However, we note this development with concern and investors should demand a higher pre-tax return from their investments to compensate for this loss on account of taxation. Anyone who works with a Discounted Cash Flow model (DCF), either on an excel sheet or in their minds in a rough calculation, should mark down the intrinsic value of the investee company a notch on account of this change in taxation.